Nvidia's $57 Billion Quarter: Why the AI Bubble Just Got Bigger—Not Burst

Nvidia crushed Q3 FY2026 expectations with $57 billion in revenue and booming Blackwell chip demand. But beneath the triumphant headlines lies a troubling paradox: circular investments totaling $53 billion, GPU depreciation concerns from Michael Burry, supply chain fragility, and unprecedented capital intensity. The earnings beat doesn't disprove the AI bubble—it reinforces it. Strong fundamentals and bubble valuations can coexist, just as Amazon was both revolutionary and overvalued in 1999.

Nvidia's $57 Billion Quarter: Why the AI Bubble Just Got Bigger—Not Burst

Nvidia's third-quarter fiscal 2026 earnings report, released on November 19, 2025, should have been a moment of vindication for AI believers. The chip giant crushed expectations with $57.0 billion in revenue—beating analyst estimates by over $2 billion—and posted adjusted earnings per share of $1.30, well above the $1.25 consensus forecast. Data center revenue alone hit $51.2 billion, up 66% year-over-year, driven by what CEO Jensen Huang called "insane" demand for the company's Blackwell AI chips.

The market responded enthusiastically. Nvidia's stock surged 6% in after-hours trading, potentially adding nearly $200 billion to its market capitalization—the largest single-day move in the company's history. Other AI chipmakers like Broadcom, AMD, and Taiwan Semiconductor rode the wave higher, and the broader tech rally that followed erased weeks of losses for the Nasdaq 100.

But beneath the triumphant headlines lies a more troubling reality: Nvidia's blockbuster quarter doesn't disprove the AI bubble thesis. It reinforces it.

Nvidia's Blackwell chips are "sold out" for 12 months—but the demand may be artificially inflated by circular investments

Nvidia's Blackwell chips are "sold out" for 12 months—but the demand may be artificially inflated by circular investments

The Numbers That Made Wall Street Cheer

Let's start with what the market celebrated. Nvidia's Q3 FY2026 performance was, by any traditional measure, extraordinary. Revenue grew 22% quarter-over-quarter and 62% year-over-year. Free cash flow hit $22.09 billion, up 32% from the previous year. The company returned $37 billion to shareholders through buybacks and dividends in the first nine months of fiscal 2026, demonstrating confidence in its financial position.

The data center segment—now accounting for nearly 90% of Nvidia's total revenue—was the star performer. The $51.2 billion in data center sales represented a 25% sequential increase, powered almost entirely by demand for Nvidia's latest Blackwell architecture. Huang reported that Blackwell chips were "sold out" for the next 12 months, with the GB300 variant accounting for two-thirds of Blackwell revenue despite being the newer of the two flagship products.

Perhaps most impressively, Nvidia provided Q4 guidance of $65 billion in revenue, smashing analyst expectations of $61.6 billion. CFO Colette Kress reaffirmed the company's projection of over $500 billion in AI chip orders spanning calendar years 2025 and 2026, suggesting demand visibility extends well into next year.

CEO Jensen Huang dismissed AI bubble concerns: "From our perspective, we see something very different"

CEO Jensen Huang dismissed AI bubble concerns: "From our perspective, we see something very different"

Huang addressed the "AI bubble" concerns directly on the earnings call, dismissing them with characteristic confidence. "From our perspective, we see something very different," he said, pointing to three transformative shifts driving AI demand: the migration from general-purpose CPUs to accelerated computing with GPUs, the integration of generative AI into existing applications, and the emergence of "agentic AI" systems that can reason, plan, and execute tasks autonomously.

The CEO's argument is compelling on its face. Six years ago, CPUs accounted for 90% of the world's top 500 supercomputers. Today, that figure has flipped, with accelerated computing representing 90% of high-performance systems. This isn't speculative future demand—it's a fundamental restructuring of the computing landscape happening in real time.

So why are we still talking about a bubble?

The Bubble Paradox: When Success Becomes the Warning Sign

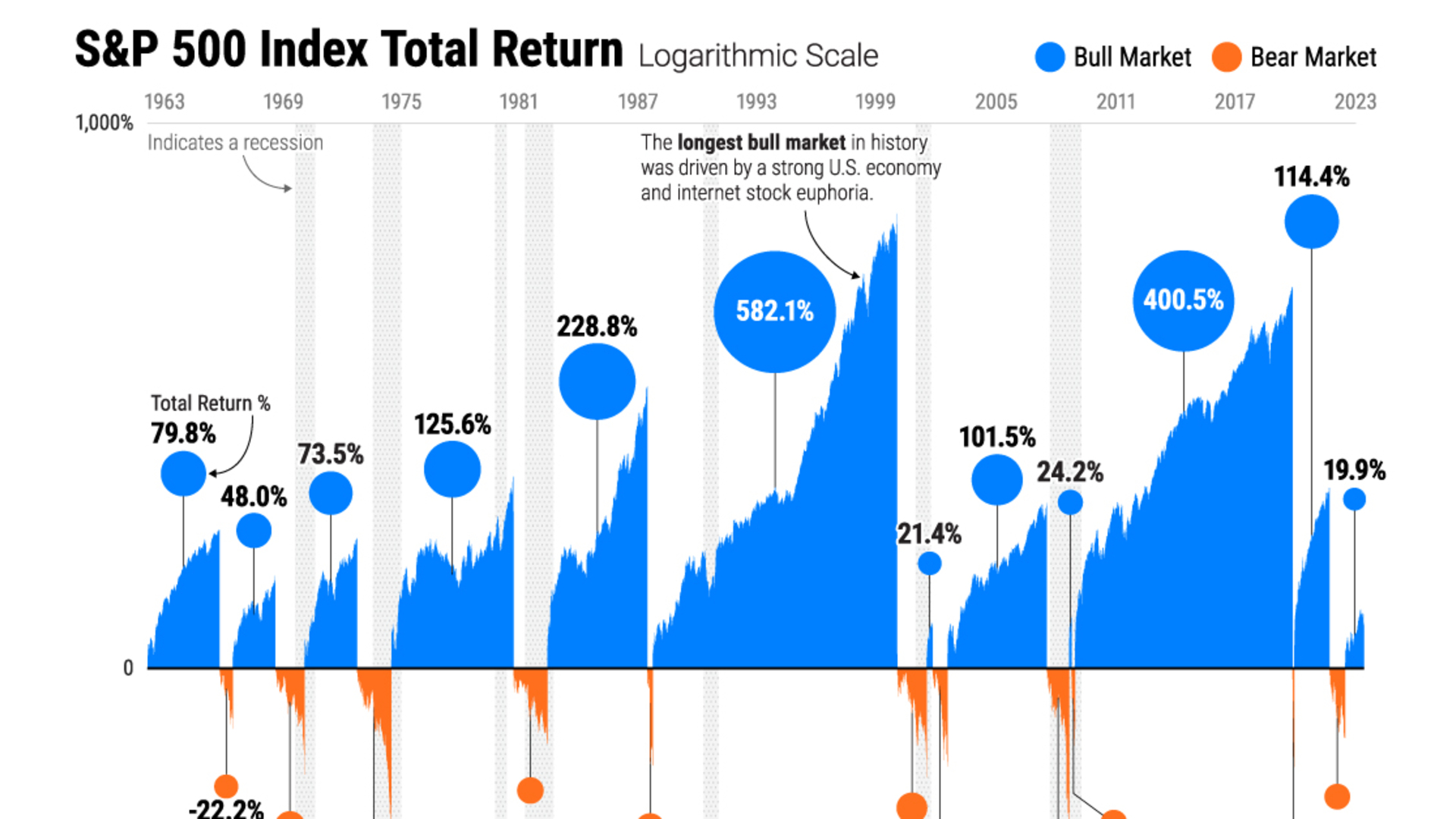

The counterintuitive truth about technology bubbles is that they're defined not by failure but by unsustainable success. The dot-com bubble produced Amazon, Google, and eBay—legitimate revolutionary companies with real revenue. The housing bubble was built on genuine demand for homes and historically low mortgage rates. Bubbles burst not because the underlying technology or asset is worthless, but because valuations, investment levels, and market expectations become unmoored from economic reality.

Nvidia's Q3 results highlight this paradox perfectly. The company is experiencing genuine, massive demand for its products. But the mechanisms creating that demand—and the financial structures supporting it—are precisely what should concern investors.

Consider the scale of investment flowing into AI infrastructure. Meta has guided for $70-72 billion in capital expenditure for 2025, with CEO Mark Zuckerberg promising "hundreds of billions" more in pursuit of "superintelligence." Microsoft disclosed $35 billion in capex, while Alphabet increased its 2025 guidance to $91-93 billion. Oracle has issued $18 billion in bonds, and Meta another $30 billion, specifically to finance AI data center buildouts.

This represents the largest coordinated infrastructure investment in modern technology history—dwarfing the fiber-optic cable boom of the late 1990s that preceded the dot-com crash. The total global investment in AI data centers is estimated to exceed $315 billion in 2025 alone, according to industry analysts tracking construction and equipment orders.

The $315 billion AI data center boom of 2025 dwarfs the dot-com era's fiber-optic infrastructure spending

The $315 billion AI data center boom of 2025 dwarfs the dot-com era's fiber-optic infrastructure spending

Here's where it gets interesting: much of this spending flows directly or indirectly back to Nvidia. The company isn't just selling chips to meet organic demand—it's actively financing the ecosystem buying those chips.

The Circular Investment Machine

Since 2020, Nvidia has invested approximately $53 billion across 170 deals in the AI sector. Many of these investments create what critics call "circular financing"—arrangements where Nvidia funds its own customers, who then use that capital to purchase Nvidia's products.

The most prominent example involves OpenAI. Nvidia announced plans in 2025 to invest up to $100 billion in the ChatGPT creator to facilitate construction of massive AI data centers. In return, OpenAI committed to purchasing and deploying millions of Nvidia GPUs. NewStreet Research analysts estimate that for every $10 billion Nvidia invests in OpenAI, it could generate $35 billion in GPU purchases or lease payments—equivalent to 27% of Nvidia's annual revenue from the previous fiscal year.

The web of circular deals extends far beyond OpenAI:

-

CoreWeave: Nvidia holds a 7% stake (valued at $3 billion as of June 2025) in this cloud service provider that supplies GPU capacity to OpenAI. Nvidia also agreed to spend $6.3 billion to purchase any cloud capacity CoreWeave can't sell to others, essentially guaranteeing demand. CoreWeave has purchased at least 250,000 Nvidia GPUs totaling about $7.5 billion.

-

Anthropic: In November 2025, Microsoft and Nvidia announced investments in the Claude AI creator. Anthropic committed to spending $30 billion on Microsoft's Azure cloud services—"powered by Nvidia"—in exchange for up to $5 billion from Microsoft and $10 billion from Nvidia.

-

Lambda and Other Neoclouds: Nvidia agreed to spend $1.3 billion over four years renting 10,000 of its own AI chips from Lambda, plus a separate $200 million deal for 8,000 more chips. Similar arrangements exist with other "neocloud" providers across the AI infrastructure landscape.

Nvidia's $53 billion in circular investments create an interconnected web where money flows back through the ecosystem

Nvidia's $53 billion in circular investments create an interconnected web where money flows back through the ecosystem

These deals aren't illegal or even necessarily inappropriate. They reflect Nvidia's strategy to vertically integrate the AI supply chain and ensure its ecosystem has access to capital and capacity. The company's investments help AI startups secure debt financing at lower rates and accelerate infrastructure deployment.

But they also create an accounting hall of mirrors. When Nvidia invests in a company that then spends that money buying Nvidia chips, is the resulting revenue a genuine arms-length transaction or something closer to vendor financing? When those purchases are recorded as backlog and used to justify forward guidance, are investors getting a clear picture of organic demand?

Critics point to parallels with the dot-com era, when companies like Cisco engaged in similar "vendor financing" to help customers purchase networking equipment. Those arrangements inflated revenue and obscured deteriorating fundamentals until the bubble burst. Michael Lewis's "The Big Short" protagonist Michael Burry has been particularly vocal about the risks, arguing that circular AI investments are creating phantom demand that will evaporate when capital conditions tighten.

Jensen Huang defends the strategy by noting Nvidia's investments are "associated with expanding the CUDA ecosystem"—the software platform that creates lock-in for Nvidia's chips. He argues these are strategic partnerships with industry leaders, not desperate attempts to prop up demand.

The truth likely lies somewhere in between. But one thing is clear: when you have to invest tens of billions in your customers to generate hundreds of billions in orders, the health of the entire ecosystem becomes frighteningly interdependent. If OpenAI's business model fails, Nvidia doesn't just lose a major customer—it takes a multi-billion-dollar equity hit. If the AI infrastructure buildout slows for any reason, the ripple effects could cascade through dozens of interconnected companies simultaneously.

The Depreciation Time Bomb

While circular investments create demand-side concerns, there's an equally troubling supply-side issue: GPU depreciation.

The debate centers on a simple question: How long do AI chips remain economically useful? The answer determines whether the hundreds of billions being invested in AI infrastructure represents productive capital formation or an expensive waste of resources.

Michael Burry has emerged as the most prominent skeptic, arguing that Nvidia's customers are extending the estimated useful life of AI chips to 5-6 years despite a product cycle where new chips are released annually or every 18 months. He estimates Big Tech could understate depreciation by $176 billion between 2026 and 2028, inflating reported profits for companies like Oracle (by 26.9%) and Meta (by 20.8%).

The implications are profound. If current-generation GPUs become economically obsolete in 2-3 years rather than 5-6, data center operators would face a "depreciation tsunami"—accelerated write-downs that would hammer earnings and force companies to either accept lower margins or continuously upgrade their infrastructure at enormous expense.

Jensen Huang himself has acknowledged the issue, stating that predecessor Hopper chips would see significant value deterioration once newer Blackwell chips ship in volume. Nvidia's rapid innovation cycle—the company is already preparing "Blackwell Ultra" for release in 2026—creates built-in obsolescence for prior-generation hardware.

Industry defenders argue that older GPUs can transition from demanding AI model training to less compute-intensive inference workloads, extending their useful life to 6-8 years. Crusoe Energy's Erwan Menard, who helped build Google's Vertex AI platform, noted that older GPUs remain profitable in their fleet due to the diversity of AI models and workloads. CoreWeave reports that older Nvidia A100 and H100 chips remain fully booked and re-contracted at near-original prices.

Michael Burry warns GPU depreciation could trigger a $176 billion accounting crisis for Big Tech by 2028

Michael Burry warns GPU depreciation could trigger a $176 billion accounting crisis for Big Tech by 2028

Stacy Rasgon, chip analyst at Bernstein, sides with the longer depreciation view, stating that "GPUs can profitably run for about 6 years" and that major hyperscalers' accounting is "reasonable." Lambda's Matt Rowe believes an effective lifespan of 7-8 years is achievable.

The lack of historical track record makes definitive conclusions impossible. The AI boom only began in late 2022, so we simply don't know yet how well current-generation chips will hold value over time. But the wide divergence in depreciation schedules—Google, Oracle, and Microsoft estimate up to six years; some neoclouds like Nebius use four years; Scaleway considers three years realistic—suggests significant uncertainty and potential for nasty surprises.

Here's what we do know: companies are financing GPU purchases with debt, often using the GPUs themselves as collateral. Private credit funds are increasingly lending against AI chips, even to speculative startups. If GPUs depreciate faster than expected, the collateral value supporting these loans evaporates, potentially triggering defaults and broader financial contagion.

Supply Chain Fragility

Even setting aside valuation concerns, Nvidia faces tangible production and supply chain challenges that could constrain its growth narrative.

The Blackwell chip family has encountered significant manufacturing hurdles. An initial design flaw required a "mask change" that lowered chip yields and delayed production timelines. More fundamentally, the advanced packaging process—particularly TSMC's CoWoS-L technology that glues multiple chips together—has become a bottleneck. TSMC is racing to expand capacity, converting existing facilities and building new ones, but the ramp-up has been "lumpy" and unpredictable.

The technical complexity of Blackwell systems compounds the challenge. The GB200 variant features power density of approximately 125 kilowatts per rack—several times higher than standard data center deployments. This has led to issues with power delivery, overheating, water cooling supply chain constraints, and even water leakage in early deployments. Some form-factor variants have been effectively canceled to focus available capacity on the highest-margin rack-scale systems.

To address supply constraints, Nvidia introduced a new Blackwell GPU called the B200A, based on a different die that can be packaged on simpler CoWoS-S technology. This provides greater production flexibility but also suggests the original roadmap couldn't be executed as planned.

Nvidia's stock surged 6% after earnings, adding nearly $200 billion in market value—the company's largest single-day move

Nvidia's stock surged 6% after earnings, adding nearly $200 billion in market value—the company's largest single-day move

Production is ramping significantly—output is expected to triple in Q1 FY2027 compared to Q4 FY2026, reaching 750,000-800,000 units. But this acceleration comes at a cost. Nvidia executives warned that gross margins could sink several percentage points to the low-70% range until production issues are fully resolved, even as the company guides for 75% margins in Q4 FY2026.

The company is also establishing domestic U.S. production, including chip packaging in Arizona and supercomputer assembly in Texas, to reduce geopolitical risk. Mass production at these facilities is expected to ramp over the next 12-15 months—adding another variable to an already complex manufacturing picture.

Meanwhile, geopolitical tensions continue to create uncertainty. China export restrictions cost Nvidia data center compute revenue in Q3, and CFO Kress expressed disappointment that "sizable purchase orders from China did not materialize." The company excluded China from its Q4 guidance entirely, effectively writing off what was once a substantial market.

What This Means for Investors

So where does this leave us?

Nvidia is unquestionably the dominant player in the most important technology transformation of the decade. The company's engineering excellence, CUDA moat, and execution discipline have created a position that rivals will struggle to challenge. The transition from CPU-based to GPU-accelerated computing is real, and it's happening faster than almost anyone predicted.

But dominance doesn't equal immunity to bubbles. In fact, the companies that dominate the growth phase of new technology cycles often become the vehicles through which bubble dynamics play out—think Cisco in the dot-com era or various homebuilders in the housing bubble.

The concerns outlined above—circular investments, depreciation uncertainty, supply chain fragility, and unprecedented capital intensity—don't mean Nvidia will crash tomorrow. They mean investors need to distinguish between the company's legitimate long-term position and the short-term fever dynamics inflating current valuations.

At current prices, Nvidia trades at a forward P/E ratio that assumes sustained hypergrowth and margin stability. Any crack in that narrative—whether from slowing demand, margin pressure from production issues, or a broader reassessment of AI infrastructure returns—could trigger swift valuation resets.

The Q3 earnings beat doesn't change this calculus. If anything, it demonstrates how strong fundamentals can coexist with bubble valuations. Amazon was an incredible company in 1999, but it still fell 95% from its peak before ultimately vindicating long-term believers a decade later.

The AI revolution is real. The investment bubble surrounding it is also real. Nvidia's latest quarter proves both things can be true at once.

Taggart Buie is an independent market analyst focused on AI and technology trends. The views expressed here are his own and do not constitute investment advice.

Sources & References

- 1. Nvidia Investor Relations. "Third Quarter Fiscal 2026 Financial Results." November 19, 2025.

- 2. Business Insider. "Nvidia Q3 Earnings Live Updates." November 19, 2025.

- 3. Fortune. "Nvidia's $24B AI Deal Blitz Has Wall Street Asking Questions About Murky Circular Investments." September 28, 2025.

- 4. CNBC. "The Register: The Circular Economy of AI Investment." November 4, 2025.

- 5. Fortune. "The Big Short Investor Closing Scion AI Bubble Depreciation Explained." November 13, 2025.

- 6. Reuters. "Tipping Point or Bubble: Nvidia CEO Sees AI Transformation While Skeptics Count Costs." November 20, 2025.

- 7. TrendForce. "Nvidia's Blackwell Begins Sample Delivery, Boosting Taiwanese AI Supply Chain Demand." August 1, 2024.

- 8. Capacity Global. "Nvidia Crushes Forecasts with $57BN Quarter as AI Chips Sell Out." November 2025.

Disclaimer: This analysis is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. Markets and competitive dynamics can change rapidly in the technology sector. Taggart is not a licensed financial advisor and does not claim to provide professional financial guidance. Readers should conduct their own research and consult with qualified financial professionals before making investment decisions.

Taggart Buie

Writer, Analyst, and Researcher